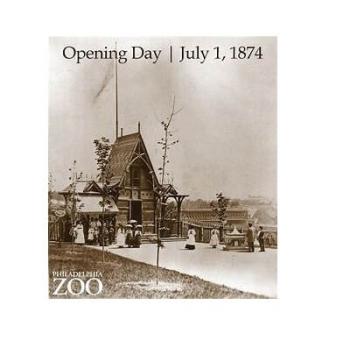

On the morning of July 1, 1874, the first zoo in the United States, the Philadelphia Zoo, opened its doors to visitors who, for a quarter or less, could visit and view the 813 animals that lived there. Today, the Philadelphia Zoo has more than twice as many animals and four times as many visitors as it had during its first year of operation.

Much more has changed in the zoo than the number of animals and visitors. Visit the Philadelphia Zoo's History Overview to learn more about the first zoo in the United States. Then have your class compare features and aspects of the first zoo with a modern zoo, using the interactive Venn Diagram tool. Ask your students to think in particular about the differences in how animals are cared for and the habitats where they live.

Once your students have considered how zoos have changed over the past century, invite them to imagine the zoo of the future. How will animals be cared for? What will the zoo look like? Who will visit the zoo? What will be the primary mission of the zoo? In small groups, students can explore these questions and then design their own zoo of the future using drawings, posters, dioramas, or a similar display technique.

National Geographic Education’s encyclopedia entry on zoos includes information on zoo history, types of zoos, zoo specialization, and conservation efforts. Related terms are defined in a Vocabulary tab. The website includes related reading suggestions, illustrations, and links to related National Geographic Education resources.

This site highlights the traveling Robot Zoo exhibit. This online exhibit explains how the robots work and how they relate to the real animals that they are modeled after. Students can even pet the animals online!

If you don't have a zoo nearby, you can use this site to find pictures and information about animals and their habitats. This site also features Classroom Resources, such as free curriculum guides and information about outreach programs.

After spending many years writing for The New Yorker, E.B. White turned his hand to fiction when his first children's book, Stuart Little, was published in 1945. White's most famous children's book, Charlotte's Web, followed in 1952. Both went on to receive high acclaim and in 1970 jointly won the Laura Ingalls Wilder Medal, a major prize in the field of children's literature. That same year, White published his third children's novel, The Trumpet of the Swan. In 1973, that book received the William Allen White Award from Kansas and the Sequoyah Award from Oklahoma, both of which were awarded by students voting for their favorite book of the year.

In honor of White’s love for children’s books about animals, have a class discussion about the ways that animals are portrayed in different fictional novels (both those by White and others). Have students do one or more of the following activities to further examine farms and farm animals, such as those in Charlotte’s Web:

- Take a class field trip to a local farm. Have students take pictures and write down the sights and sounds of the farm. After returning to the classroom, have students compile a class scrapbook that highlights the different animals at the farms and the most important things learned on the field trip.

- Students can create Acrostic Poems about a farm animal of their choice, share their poems with the class, and then create a classroom bulletin board showcasing all of the students’ favorite farm animals and information about each one.

- Have students create a Venn Diagram comparing and contrasting the farm with the city, farm life with city life, or two different farm animals. This activity can also be followed up by writing a Compare and Contrast Essay as a part of a longer activity.

- Compare the book version of Charlotte’s Web to the movie version. Then, use the Compare and Contrast Map or Venn Diagram to discuss the similarities and differences between the two.

This site includes stories about E.B. White's life and Charlotte's Web, Stuart Little, The Elements of Style, and Trumpet of the Swan.

Read about E.B. White, author of the cherished children's classic Charlotte's Web, Stuart Little, and The Trumpet of the Swan.

Find out information about E.B. White, Charlotte’s Web, and take part in some “fun and games” related to the book and movie.

Joel Chandler Harris is best known for his Uncle Remus stories. Harris collected the Uncle Remus tales from the stories shared by slaves. His use of phonetic dialogue in his stories allowed later authors to use vernacular in their renditions of regional tales. Harris's stories remain a good example of regional folk literature from the American South.

One striking aspect of Harris' stories is that in conveying the regional dialect the dialogue is written phonetically, which lends itself to oral reading of the stories. This vividly evokes the stories' original cultural milieu. Select a short segment of Uncle Remus with prominent dialogue and read it aloud to your students. Then read a segment from another book that features a different type of phonetic dialogue, such as The Witches by Roald Dahl, and listen to a Gullah Tale. After reading the three different examples of phonetic dialogue, have students use the interactive Venn diagram to compare them.

One thing all three examples have in common is that they render dialogue that has a vivid sound and feel. Challenge students to write a brief dialogue that might occur between themselves and a friend or parent. Encourage them to pay attention to phrasing and vocabulary, so that the dialogue sounds realistic. Next, have them exchange papers with a partner and read each other's dialogue aloud. Did the dialogue sound the same aloud as they imagined it when they wrote it? They should then revise any parts of the dialogue that did not sound realistic. They can repeat this process until they have a realistic dialogue.

This site provides information about the life of author Joel Chandler Harris, as well as links to the books that made him famous.

Links from this site take readers to songs and sayings by Harris.

In this Scholastic workshop, students hone their storytelling skills. There are online activities, examples, and practice opportunities included in this resource.

This resource offers examples of folk tales in both English and Gullah, a phonetically written language. Students can hear folk tales read aloud in both languages.

In 1941, the United States forces at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, were taken by surprise when Japanese warplanes began to drop bombs on the city and naval base. Hundreds of soldiers and civilians were killed during the raid, and the Navy suffered the loss of a great number of ships and other military hardware. This event marked the American entrance into World War II.

On December 7, 1941, "a date which will live in infamy" in the words of President Franklin Roosevelt, many Americans were called upon to act as heroes. Countless Americans gave their lives in defense of our country and its citizens in Pearl Harbor. Similarly, the surprise attacks on America on September 11, 2001, called for heroic acts of selflessness from ordinary citizens, as well as firemen, police, military personnel, and other government workers. Ask students to compare these two events using the interactive Venn Diagram. How are they alike? How are they different?

How did each event change American citizens' perspectives on war and the need for war? How did the two different Presidents of the United States react? What was different about the media coverage?

The class could be divided into groups to brainstorm various aspects of this discussion and then report back to the class as a whole.

This resource from the National Archives includes the typed first draft of President Roosevelt's War Address to Congress with his handwritten edits. An audio excerpt of the speech is also available.

This page by the Naval Historical Center features a historic overview of the Pearl Harbor raid and its aftermath.

This Teacher Tool Kit contains a variety of primary and secondary sources that can be used to supplement your curriculum instruction and offer the most direct explanation of the events surrounding the attack on December 7, 1941.

This page from the Library of Congress includes a copy of the U.S.S. Ranger's Naval dispatch from Commander in Chief Pacific announcing the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

Louisa May Alcott, author of Little Women and other novels, was born on this date in 1832. Alcott wrote several novels under her real name and also penned works under a pseudonym. Her very first novel, The Inheritance-written when she was 17-wasn't published until 150 years after she wrote it, when two researchers discovered it in a library in 1997.

Little Women is partly autobiographical. Alcott used many of the events of her own life as fodder for her writing of this and her other novels. In fact, most scholars believe that the character of Jo March closely resembles Louisa May Alcott. It is not unusual for authors to take incidents from their own lives and use them in their fiction.

Ask students to brainstorm and write in their journals important events and names of people from their lives that might serve as the beginning point for an interesting story, poem, or longer work. Students can then use the interactive Bio-Cube to plan their story. There are more tips available to learn more about the Bio-Cube. An alternative might be to ask students to write about a memorable person in a nonfiction essay format. (This could be submitted to Readers' Digest, which has a feature of this type in each issue). Another alternative would be to have students research the life of Alcott and then read some of her novels to develop a list of those people and incidents from her own life that appear in her fiction.

Information about Alcott's life and work is found at this site. Links provide information about various aspects of her life. The site also includes a virtual tour of the house where Louisa May Alcott grew up.

From the textbook site for the Heath Anthology of American Literature, this site provides complete biographical information, critical material, and links to related resources.

This site for the American Masters film biography of Louisa May Alcott offers extensive information about Alcott's life and work, including historical photos and a multimedia timeline.

The Library of Congress offers this resource with information about Alcott's life, images, and excerpts from the writings of Alcott's father regarding her birth and early childhood.

William Blake was born on November 28, 1757, in London, England. While best known for his poetry, including The Songs of Innocence and The Songs of Experience, Blake was also an accomplished artist and engraver who illustrated many of his own poetic works. As a believer in the power of human imagination, Blake influenced those poets and writers who would later be called the Romantics. He died on August 12, 1827, with no money and little recognition.

In his artwork, Blake invented names, faces, and actions that personified abstract concepts. His character, Urizen, for example, represented law and order, and Blake often drew him as a bearded old man.

As a class, brainstorm a list of grade-appropriate abstract concepts, such as "freedom," "anger," "peer pressure," "frustration," etc. Then, have students choose one and write down all the words that they associate with that concept. Finally, students should personify that concept either through a drawing or through a story told about the character who personifies that concept. See "Poetstanding" the Poem for examples of Blake's personification.

Blake's Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience also work well to develop students' skills at comparing and contrasting. Have students read and complete a Venn Diagram for The Tyger and The Lamb. Elementary students can identify words and phrases that are similar and different in the poems, while older students should be able to identify differences in tone and theme.

This hypermedia project is sponsored by the Library of Congress and the NEH; it contains everything that you might want to know about Blake, including biographies, written work, visual art, and criticism.

This site has 10 full-color images of Blake's paintings and engravings. Show them to students to introduce a discussion on tone; they are extremely powerful pieces.

This resource for high school students reviews the various characters in William Blake's personal mythology using images and text.

The New York Public Library Digital Gallery offers images of the original versions of three books by Blake, for which he created the text and illustrations and printed the books.

World Hello Day began in 1973 to promote peace between Egypt and Israel. There are now 180 countries involved in the attempt to foster peace throughout the world, and letters supporting the effort have been written by people such as John Glenn, Colin Powell, Kofi Annan, and the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF).

Throughout history, important leaders and institutions have used letters to make their beliefs known and to convince others of the importance of peace and unity. Invite your students to study one of the letters below for its message promoting peace in some way:

- Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.'s Letter from Birmingham Jail

- An Open Letter from American Jews to Our Government

- Yes, Virginia, There Is a Santa Claus

Have students examine one of the letters to determine the author's purpose in writing, and to identify words and phrases that were used to make the letters more meaningful to the reader. Then, have them use the ReadWriteThink Letter Generator to write a letter of their own promoting peace. More tips are available about using the Letter Generator. Students may choose to write about world conflict, or they may choose to write about issues closer to home, such as bullying or peer conflicts.

This site provides a wide range of materials for students at all grade levels. Resources include information about the Nobel Peace Prize laureates, a timeline, and a series of informational articles.

The Jane Addams Peace Association furthers the cause of peace by selecting and awarding children's literature that promotes the cause of peace, social justice, world community, and equality.

The material in this website will enhance social studies and literature lessons in all primary grades. Your students will want to revisit this site throughout the school year.

This site lists eight easy activities designed to celebrate world language. The activities are perfect for ESL and bilingual classes and are beneficial to all primary school students.

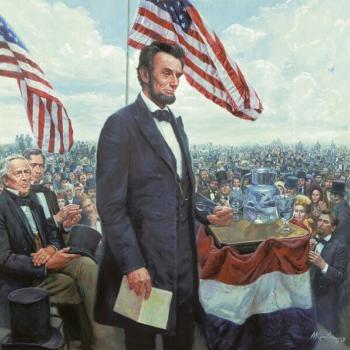

Invited to speak at the consecration of a memorial honoring the dead at Gettysburg, Abraham Lincoln delivered one of the most well-known speeches in American history. While the speech is extremely short-just 267 words-Lincoln used the opportunity both to honor the sacrifice of the soldiers and to remind American citizens of the necessity of continuing to fight the Civil War. The Gettysburg Address stands as a masterpiece of persuasive rhetoric.

Middle and high school students should be able to do a close reading of the Gettysburg Address by using the Pre-AP strategy called SOAPSTone. Print a copy of the Address. Then, ask students to identify and discuss the following:

While younger students may find the text of this speech too advanced, they can certainly begin the process of identifying the purpose, structure, and means of persuasive speech and writing.

This site contains the full text of the Gettysburg Address as well as rough drafts and the only known photo of Lincoln at Gettysburg.

The Library of Congress offers this collection of over 30,000 items by and about Abraham Lincoln. The collection includes letters and other items from Lincoln's presidency, as well as sheet music, pamphlets, and other items that reflect Lincoln's life and times.

This site ranks the top 100 American speeches of the 20th century as determined in a nationwide survey. The speeches were rated on two criteria: rhetorical artistry and historical impact.

Before the invention of the railroad, people used local "sun time" as they traveled across the country. With the coming of the railroad, travel became faster, exacerbating the problems caused by the hundreds of different "sun times." At the instigation of the railroads, for whom scheduling was difficult, the U.S. Standard Time Act was passed, establishing four standard time zones for the continental U.S. On November 18, 1883, the U.S. Naval Observatory began signaling the new time standard.

After learning about different time zones, ask your students to plan a video conference with a class from a different country or from a different time zone in the United States. As they plan, ask students to:

- Use the World Time Engine to find the best time to schedule this meeting.

- Research the country or state of the students with whom they will video conference and brainstorm a list of questions and topics for discussion. The place selected can be coordinated with topics they are currently studying.

- Brainstorm a list of topics about their own town or country that they would like to discuss. Alternatively, they could brainstorm a list of questions they think students from the other time zone might ask them.

- Use a time zone map to figure out how many time zones they would have to travel through to have this conference if video conferencing hadn't been developed.

If you decide not to carry out an actual video conference, alternatively, divide your class into two groups and allow them to conference with one group playing the role of the class from another time zone.

This page from the Library of Congress' American Memory site offers excellent information and primary documents about the history of standardized time.

Students take a journey from ancient calendars and clocks to modern times, at this NIST Physics Laboratory website.

This site provides a clickable map that gives the official time for each time zone in the U.S.

BBC News looks at time zones--how they are worked out, why they cause so many arguments, and how they affect us all.

In 1804, at the request of Thomas Jefferson, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark set out from St. Louis with their 33-member team to explore the American West. By mid-November of 1805, guided and aided much of the way by a young Shoshone woman named Sacagawea, they arrived at the Pacific Ocean. Their accounts, describing the American Indians they met, the wildlife they saw, and the physical environment they withstood, paved the way for the great western expansion.

Think for a moment about how descriptive Lewis and Clark needed to be in their writings for an audience back East who had never seen, or imagined, what they were seeing. This is a wonderful opportunity to practice descriptive writing with your students.

Depending upon your school's technology, you can have students look at Kenneth Holder's paintings of various scenes from the Lewis and Clark trail, available here. If this is not possible, print out landscape scenes-or slides from your own vacation-that are vivid in their details. Then, ask students to write words and phrases that describe what they see, what they imagine they might hear, etc. Remind them that they are writing for an audience that has never seen these pictures before. Ask students to transform their notes into a descriptive paragraph as if they were a member of the Lewis and Clark expedition. Last, ask students to return to a piece that they have already written this year and revise it by adding more sensory words and phrases.

This portion of the PBS website dedicated to the Lewis and Clark expedition is an interactive story where portions of the journey are recounted and students are expected to make a choice about what Lewis and Clark should do next.

This is a short, easy-to-read article on York, William Clark's slave, who played a vital, but underappreciated, role on the expedition.

This National Geographic site tries to uncover some of the mystery surrounding this teenage Shoshone woman who acted as an interpreter and guide for the expedition.

This site, dedicated to Lewis and Clark, includes an interactive journey log, timeline, games, and information about supplies used and discoveries made by the Corps of Discovery.