Before the invention of the railroad, people used local "sun time" as they traveled across the country. With the coming of the railroad, travel became faster, exacerbating the problems caused by the hundreds of different "sun times." At the instigation of the railroads, for whom scheduling was difficult, the U.S. Standard Time Act was passed, establishing four standard time zones for the continental U.S. On November 18, 1883, the U.S. Naval Observatory began signaling the new time standard.

After learning about different time zones, ask your students to plan a video conference with a class from a different country or from a different time zone in the United States. As they plan, ask students to:

- Use the World Time Engine to find the best time to schedule this meeting.

- Research the country or state of the students with whom they will video conference and brainstorm a list of questions and topics for discussion. The place selected can be coordinated with topics they are currently studying.

- Brainstorm a list of topics about their own town or country that they would like to discuss. Alternatively, they could brainstorm a list of questions they think students from the other time zone might ask them.

- Use a time zone map to figure out how many time zones they would have to travel through to have this conference if video conferencing hadn't been developed.

If you decide not to carry out an actual video conference, alternatively, divide your class into two groups and allow them to conference with one group playing the role of the class from another time zone.

This page from the Library of Congress' American Memory site offers excellent information and primary documents about the history of standardized time.

Students take a journey from ancient calendars and clocks to modern times, at this NIST Physics Laboratory website.

This site provides a clickable map that gives the official time for each time zone in the U.S.

BBC News looks at time zones--how they are worked out, why they cause so many arguments, and how they affect us all.

In 1804, at the request of Thomas Jefferson, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark set out from St. Louis with their 33-member team to explore the American West. By mid-November of 1805, guided and aided much of the way by a young Shoshone woman named Sacagawea, they arrived at the Pacific Ocean. Their accounts, describing the American Indians they met, the wildlife they saw, and the physical environment they withstood, paved the way for the great western expansion.

Think for a moment about how descriptive Lewis and Clark needed to be in their writings for an audience back East who had never seen, or imagined, what they were seeing. This is a wonderful opportunity to practice descriptive writing with your students.

Depending upon your school's technology, you can have students look at Kenneth Holder's paintings of various scenes from the Lewis and Clark trail, available here. If this is not possible, print out landscape scenes-or slides from your own vacation-that are vivid in their details. Then, ask students to write words and phrases that describe what they see, what they imagine they might hear, etc. Remind them that they are writing for an audience that has never seen these pictures before. Ask students to transform their notes into a descriptive paragraph as if they were a member of the Lewis and Clark expedition. Last, ask students to return to a piece that they have already written this year and revise it by adding more sensory words and phrases.

This portion of the PBS website dedicated to the Lewis and Clark expedition is an interactive story where portions of the journey are recounted and students are expected to make a choice about what Lewis and Clark should do next.

This is a short, easy-to-read article on York, William Clark's slave, who played a vital, but underappreciated, role on the expedition.

This National Geographic site tries to uncover some of the mystery surrounding this teenage Shoshone woman who acted as an interpreter and guide for the expedition.

This site, dedicated to Lewis and Clark, includes an interactive journey log, timeline, games, and information about supplies used and discoveries made by the Corps of Discovery.

Today, the United States honors those soldiers who have fought for their country in military service. Across America, ceremonies are held to commemorate the efforts of our armed forces past and present, and to remind us of both the strength and the compassion of our country.

Have students write biographical poems about a soldier by completing each of the following lines of the poem. This classroom activity is adapted from a lesson plan by Nancy Haugen of Arizona.

- Line 1: Soldier

- Line 2: Four words describing what a soldier is expected to do (teachers can specify that the words be adjectives, gerunds, etc.)

- Line 3: Who feels . . .

- Line 4: Who needs . . .

- Line 5: Who fears . . .

- Line 6: Who loves . . .

- Line 7: Who thinks . . .

- Line 8: Who believes . . .

- Line 9: Synonym for "soldier"

This project, from the Library of Congress's American Folklife Center, is a collection of interviews and documentary materials highlighting veterans' experiences over much of the 20th century.

This page, from the Department of Veteran Affairs, provides links to resources on the history of the holiday, photographs of past celebrations in our nation's capital, and other media used to promote the holiday.

This site provides information about the VFW's programs and activities around the country. The VFW's stated mission is to "honor the dead by helping the living."

Students can use these resources to research veterans and discuss the concept of patriotism.

In 1938, as Hitler began to dominate the lives of the Jewish population of Germany, Nazi soldiers were ordered to destroy Jewish stores and homes on what became known as Kristallnacht, or the Night of Broken Glass.

Many of the lessons associated with a study of Kristallnacht and the Holocaust focus on the incredibly vicious treatment of the Jews at the hands of Hitler and the Nazis. It is difficult to get students to understand how it was possible for the leaders of Germany at the time to wreak havoc on a segment of the German citizenry without others coming to their aid or rescue. To facilitate students' understanding, a journal prompt asking them to recall a time when they failed to come to the assistance of someone who needed help could be used at the beginning of the class period. An alternative would be to read "The Good Samaritan" from Rene Saldana's story collection Finding Our Way, in which a young man wrestles with just this situation.

This resource discusses the events leading up to Kristallnacht. Links to books used as sources are included.

Photographs and other historical documents about Kristallnacht detail the horror and destruction of that night.

This map, from the Florida Center for Educational Technology's A Teacher's Guide to the Holocaust, provides information about the more than 200 synagogues destroyed during Kristallnacht. Links to timelines and other pieces of information are also at this site.

Here are some strategies and resources to guide you in teaching this topic from Echoes & Reflections.

Bram Stoker, the author of Dracula, was born on this date in 1847. Dracula, originally published in 1897, has become the basis for many films, TV shows, and other novels over the more than 100 years since its publication.

In this novel, Bram Stoker depicted many of the superstitions about vampires that were prevalent in his era. Today, we have superstitions about many things besides vampires. Brainstorm with students the superstitions they know. Begin by offering some that will be familiar to many students, such as bad luck symbols (e.g., black cats, breaking a mirror, walking under a ladder) or good luck symbols (e.g., finding a penny, four-leaf clovers) and ask students to discuss how these superstitions might have had a basis in reality (for instance, it is good sense NOT to walk under a ladder, for safety's sake). Break students up into small groups and have them research one of the superstitions to determine its country of origin and its original meaning or purpose. Then, students can use the interactive Mystery Cube to write a mystery story featuring their superstition. More tips are available on how to use the Mystery Cube.

This site provides information on Bram Stoker and brief essays on his sources and influences. The site also includes resources on vampires, Vlad the Impaler, and Van Helsing.

This page provides biographical information on Stoker, links to other sources on the author, and a collection of e-texts of his writings.

This page, from author S.E. Schlosser's American Folklore site, features a collection of folk tales focused on the supernatural. The stories are part of a large collection of folk tales from throughout the United States.

This site lists versions of Dracula from the original in 1897 through editions printed in the 1990s. Thumbnail images of the cover of each edition show how the depiction of Dracula has changed.

On November 5, 1872, Susan B. Anthony cast a ballot in the presidential election, though women at the time were prohibited from doing so. Two weeks later, she was arrested, and the following year, she was found guilty of illegal voting. It would take another 50 years until the Nineteenth Amendment, passed in 1920, would grant women nationwide the right to vote.

Two of the most important lessons that we can draw from Susan B. Anthony's experiences are to understand the effects of prejudice and to appreciate the courage of acting on one's convictions.

So, on this day, grant special privileges to an arbitrarily designated group in your classroom: people wearing, say, the color red, or blondes, or people whose names start with S. These privileges could include a treat, a special hall pass, etc. You should not let anyone in on why you have singled this group out. Let the privileges-and the complaining about them-continue for a while. Then, ask students to write about how they felt during the simulation. Ask them to focus on the fairness of your actions in singling out this group for special treatment.

The next step is to ask students to consider exactly what they might be willing to do to change an unjust law. Remind them that Anthony and other women's rights activists went to jail to protest an injustice. Have students write about what they might feel strongly enough about to protest and what actions are justified in order to change that injustice.

This article describes Anthony's trial. Interestingly, she was not allowed to testify in her own defense because of her gender, and the judge entered the guilty verdict without allowing the jury to deliberate.

This site honors Americans who have "gone the extra mile" by volunteering their time and effort to the cause of improving the lives of others. This site tries to pass on the spirit of volunteerism and commitment.

The American Memory Project includes this timeline of important events in the history of the women's suffrage movement.

This online companion to the Ken Burns documentary of the same name uses text, audio, and images to explore the women's suffrage movement, focusing on Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

In the United States, Halloween is celebrated on October 31. The holiday has its roots in the pre-Christian Celtic festival of Samhain. It was Christianized in the 9th century as "All Hallows' Eve," which precedes the Roman Catholic celebration of All Saints' Day on November 1.

- If you have Internet access in your class or school, assign one common aspect of Halloween (e.g., costumes, pumpkins, witches) to a group of students and ask them to search for information about how that aspect came to be a part of Halloween tradition.

- Have students make a list of the characters from a text that they are currently reading (or from texts read earlier in the year). Ask students to create masks or costumes that represent one of the characters from the text. Each student could then be asked to deliver a short monologue as that character to a small group.

- Ask students to write a narrative describing their best Halloween ever, an expository essay that tells how to plan a Halloween celebration, or a spooky Halloween mystery story. They can plan the last one using the interactive Mystery Cube tool. Helpful information can be found on the Mystery Cube page.

This online magazine is a great place to research the history of Halloween and includes a link for teachers to find a few classroom activities.

Elementary students in the United States and Canada share their language arts activities in this collaborative Internet project about autumn. Students can view the work and use it as a model for their own projects. Don't miss the Haunted House showcased in Mrs. Silverman and Miss Sowa's class.

This page from KidsReads.com provides an annotated list of books about Halloween.

This page from the Library of Congress American Memory website features primary documents related to Halloween, including interviews, folk tales, and audio files. Some highlights include images of magician Harry Houdini, first-hand accounts of Halloween tricks of the past, and spooky songs.

Dr. Jonas Salk was born in New York City on October 28, 1914. In 1953, Salk announced that he had successfully developed a polio vaccine, reducing the number of deaths from the disease in the U.S. by 95%. During the last 10 years of his life, Salk focused on AIDS research. Salk died in 1995.

After learning about Dr. Jonas Salk, ask your students to interview a family member or somebody they know who remembers when polio was endemic. There are many stories related to the history of the disease in the United States-from the first people to be vaccinated to those who had the disease themselves. Students can share their stories and interviews in class. If students are unable to locate enough people who can share memories of the disease, visit the Share Your Story section of the March of Dimes website. Take advantage of the stories to talk about the difference between fact and opinion, making note of the information from the stories on the board. Compare the facts from the stories to the facts available in reference materials. If desired, students can submit their family stories to the appropriate area of the March of Dimes website.

This page from the Academy of Achievement provides an excellent biography on Salk, including video of his interviews and photographs.

Have your students read the comic-book style story of how Albert Sabin and Jonas Salk developed a vaccine for polio.

This website aims to increase awareness of polio and to raise the funds needed to eradicate the disease. The site offers an excellent history of the disease from 1580 BC to the present.

From the Eisenhower Library, this website provides online access to many of the primary documents related to the polio vaccine, including presidential statements and official government documents.

Pablo Picasso, a dominant figure in 20th-century Western art, was born on October 25, 1881, in Malaga, Spain. In painting and sculpting, he was one of the creators and popularizers of the Cubist style. Though Picasso was not typically considered "political," one of his most celebrated works, Guernica, memorializes the destruction of the Basque town of Guernica during the Spanish Civil War. He died on April 8, 1973.

For high school students, select a Picasso Cubist portrait from one of the Websites. If you have a projector, you can project the image from the website onto a screen. If not, you can make a color copy of the portrait or arrange for your class to visit the computer lab.

Give students about one minute to view the piece, then ask them to write their impressions and share them with a partner. Next, show students a Picasso portrait that does not employ the Cubist style (most of his work prior to 1905) and ask them to describe the person's face and body. Then, share with students the main concept of Cubism, which is to capture the essence of a subject by showing its multiple perspectives all at the same time. Show students another Picasso Cubist portrait and ask them to describe the person in the portrait this time. Is this person recognizable? What perspectives are shown? After this discussion, students can have fun creating their own Picasso-style art using the interactive Picassohead.

This website is a virtual one-stop shop for everything related to Picasso. The site not only contains biographical information about Picasso, but also offers thousands of full-color images of his work.

This website, developed by Maryland Public Television, highlights several Picasso paintings and provides analyses of his works. The section called Vantage Point offers materials for using Picasso to enrich mathematics, social studies, and language arts curricula.

This page features the text of the 1973 New York Time article announcing the death of Picasso. Students can compare the 1973 perspective of the painter and his work with the modern perspective.

The Guggenheim Museum provides examples of Cubist art from its collection, including some of Picasso's works. Also included is a definition of Cubism.

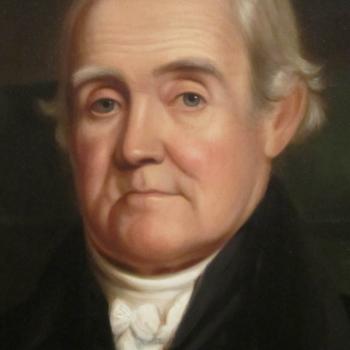

Noah Webster, called the father of the American dictionary, was born on October 16, 1758, in Connecticut. Believing that American students should not have to use British textbooks, he wrote A Grammatical Institute of English Language, which became the main source for spelling and grammar in the United States. He then began work on the first American dictionary, An American Dictionary of the English Language, which contained nearly 70,000 words by the time it was completed in 1828.

To celebrate Webster's birthday, try this variation of the popular board game Balderdash:

- Divide your class into groups of five or six. You will need one dictionary per group and a stack of blank paper cut into strips of about two inches each.

- One student in the group quickly scans through the pages in the dictionary and identifies a word that he or she believes no one has ever heard before. That student reads the word aloud and spells it. The other students in the group write down a definition for the word, either the real definition or a made-up definition that might fool others into thinking it is the real definition.

- The student with the dictionary writes the real definition on a slip of paper and then collects all the slips from the group. The student then reads each of the definitions created by others in the group, as well as the real definition.

- The students in the group then individually choose which of the definitions they believe is real. Points are awarded as follows: two points if you select the correct definition and one point for each time that someone else selects the definition that you wrote.

- Points are totaled and the next person in the circle selects a word from the dictionary. The game can continue for as long as you like.

This website offers a brief biography of Webster and his views on various political and educational topics.

The online version includes audio pronunciations, a thesaurus, Word of the Day, and word games.

This online dictionary includes illustrations and is an excellent resource for K–3 readers.